Dr. Vanderwaerden: Buprenorphine Maintenance versus Placebo or Methadone Maintenance for Opioid Dependence (Review)

Click this link to view a recording of the presentation.

Dr. Vanderwaerden presented a recent Cochrane Review of the literature comparing buprenorphine to methadone and to placebo as maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. The authors assessed all trials of the two medications which met their inclusion criteria. The outcomes they examined were retention in treatment, use of illicit opioids, other substance misuse, criminal activity and mortality.

By way of background, it's worth recalling several key pharmacological and legal differences between methadone and buprenorphine. First, pharmacologically, methadone is a full agonist at opiate receptors and as such is associated with the full range of opiate toxicities. Its half-life is also relatively short, requiring once-daily dosing. Buprenorphine, on the other hand, is only a partial agonist and therefore appears to be less toxic; it may also pose fewer risks for diversion, particularly when combined (as it is in one of the more popular formulations) with naloxone. Its half-life is also considerably longer, making every-other-day dosing possible. These pharmacological differences are overshadowed by the enormous legal differences. While methadone may only be dispensed according to a highly detailed procedural code in specially certified clinics, which are very difficult to establish and maintain, buprenorphine can be dispensed in a doctor's office by any licensed physician who has successfully completed an eight hour course.

In their review of the literature, the authors of this review found that patients on buprenorphine were less likely to be retained in treatment (relative risk 0.83, 95% CI 0.72-0.95). They found no significant differences in the other endpoints they examined (see above).

This result, as Dr. Abramowitz pointed out in our discussion, should be interpreted with some caution. One take, endorsed by the authors, might be that methadone is just clearly a better drug. However, if one recalls the immense differences in context between methadone and buprenorphine prescribing, it's easy to believe that this might all just represent sampling bias. Buprenorphine treatment is generally far less rigidly constrained than methadone treatment for the reasons cited above, and the lower retention in treatment may reflect participation by less committed patients because of lower barriers to entry rather than reduced efficacy.

Finally, it is worth remembering that because of the difficulties in establishing methadone clinics, the choice is often not between buprenorphine and methadone, or even buprenorphine and placebo, but between buprenorphine and nothing, in which case buprenorphine is clearly the better choice.

Dr. Litwin: Bupropion-SR, Sertraline, or Venlafaxine-XR after Failure of SSRIs for Depression

Click here to watch a recording of the presentation.

Dr. Litwin (in spirit) presented a segment of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial. STAR*D was an enormous and complicated trial funded entirely by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), which sought to establish the best practices for treating resistant depression with medications. It began with an observational study of citalopram, after which patients who did not experience remission (pre-defined as a particular score on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, or HRSD) were then randomized to groups testing different second, third and even fourth-line therapies. A good synopsis of the study design is available here.

The article (published in the NEJM in 2006) reported the results of the second level of the STAR*D trial. At this level, patients who had not experienced remission with citalopram or been unable to tolerate its side effects were randomized in a 1:1:1 fashion to receive open-label sertraline (another SSRI), bupropion (an inhibitor of norepinephrine and dopamine re-uptake,) or venlafaxine (an inhibitor of sertraline and norepinephrine uptake for 14 weeks.

The remission rate in all groups was about 25%, and there was no statistically significant difference in remission rates or cumulative side-effect burden between groups.

Some interesting points came up in the discussion of this article. Dr. Remler pointed out that the lack of a placebo group makes it impossible to judge whether any of these agents had any specific efficacy, or whether they all functioned essentially as placebos. This question is particularly interesting given the identical results achieved with three pharmacologically distinct agents; if one were to encounter a trial, say, of atorvastatin, nitroglycerin and vancomycin for the treatment of urinary tract infections caused by E. coli which reported a 25% remission rate, we would probably conclude that none of them did anything and that the natural history of the disease was that 25% of patients have spontaneous remission.

Dr. Hicks was impressed by the creativity the investigators displayed in designing their study to balance scientific rigor with real-world clinical practice. The STAR*D researchers put together a sophisticated and elegant design which combined the power of randomization with the exigencies of clinical care to produce results which, however one interprets them, are clearly much more easily generalizable than those of many other studies in this area.

Finally, Dr. Abramowitz emphasized that the original intent of the STAR*D group was fundamentally pragmatic. They set out to answer a question of immediate, daily clinical relevance to all psychiatrists and primary care physicians: what do you do when your first-line SSRI fails? Because of their creative study design, their results can give us confidence that similar benefits can be expected from any of the switches they studied, and that the decision can safely be made on the basis of cost and side effects.

Dr. Alexander: Comparative Effectiveness of Weight-Loss Interventions in Clinical Practice

Click here to watch a recording of the presentation.

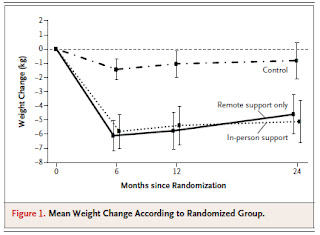

Dr. Alexander presented a very recent trial comparing two interventions to increase weight loss in primary care. Both were complex interventions which employed trained health coaches using motivational interviewing techniques and aimed to promote stustainable weight reduction through changes in behavior. Both involved a specially designed website containing various learning modules and motivational tools which study participants were encouraged to use. The main difference between the two interventions was that in one the health coaches actually met with the patients in person, whereas in the other most contacts were by telephone. These intervention groups were compared to a control group in which weight loss was self-directed.

As can be seen from the author's tabulation of their results (right) both the interventions were associated with modest but significant weight loss relative to the control group. Interestingly, however, there was not much difference between the group which received in-person support and the group receiving only remote support.

These results, as Dr. Hicks pointed out in our discussion, are encouraging. They suggest that remote interventions such as this one, which are easier to conduct because of their flexibility, may be as effective as more time and labor-intensive interventions involving lots of personal counselling.

No comments:

Post a Comment